The great outdoors, selfishness, and of course, death

I just got back from a short camping trip. Though, despite our having slept in a tent on the ground and cooking very simple meals on a little propane stove, there is a part of me that is struggling to label the experience as “camping”. It isn’t exactly how I remember “camping” looking or feeling, and it certainly didn’t sound how I remember “camping” sounding. We heard lots of music, humming and grumbling generators, thunderous belching and potentially embarrassing conversations from neighboring campsites bleeding into the night.

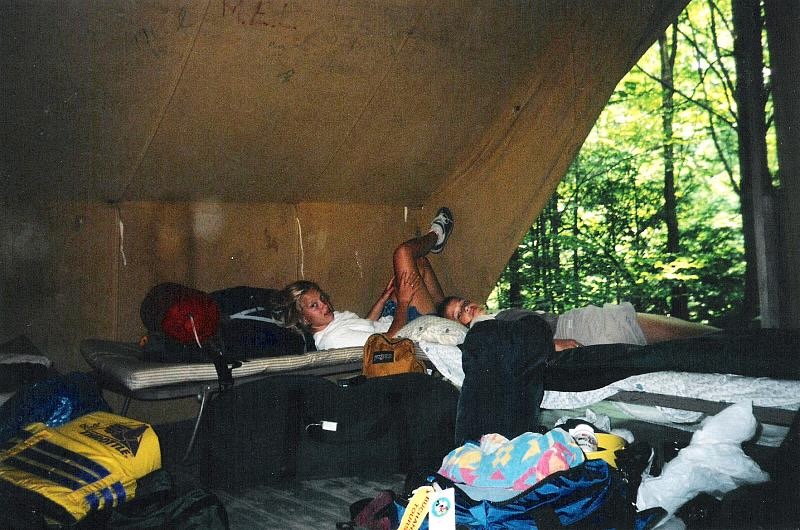

I still remember my first camping experience, thanks to the Girl Scouts of Western New York. The images in my head are fuzzy, to be sure, but I do recall the dark, shining wood inside The Brownie Lodge—the camping facility for Camp Seven Hills’ youngest campers. If I was a Brownie, then I must have been seven or eight. It was a three-nighter—that was the longest stay permitted for young Brownies. I remember being in the top bunk, near the window: a shaft of dusty sun illuminating the gray metal tubing that made up the frames of the bunk beds, the aged and yellowing mattresses with navy blue stripes beneath my little sleeping bag, which I think was green. The next year I was a Junior, and was assigned to the Highlands, a string of canvas platform tents in the woods not far from the Brownie Lodge. That was the year I struggled with intense separation anxiety (so I must have been nine), and carried around a photo of my parents with me at all times, clutched in my hand. At night, I’d frequently click on my flashlight and focus the beam on their faces, hoping they were still alive, feeling like I myself might die if I could not see them or speak to them soon. The next summer, still struggling with unpleasant degrees of homesickness even at sleepover parties, I opted to stay home. Maybe it was that summer that I slept in the lawn chairs on my friend Ellen’s back deck, under the stars. It is her blond hair I recall in the top bunk next to me in the Brownie lodge, too. We were, after all, in the same Girl Scout troop, and friends since our first days on Earth.

When I wasn’t at Camp Seven Hills, my sisters and our friends and I camped in our yard—this was easy given that we grew up in rural Western New York, surrounded by woods. My mom bought us a beige-colored tent at BJ’s, which we pitched at the top of the hill near the small pines. One night before crawling into our sleeping bags, we sat around the fire my dad built and stuffed ourselves with toasted marshmallows, my friend making a new record with fourteen.

Eventually I returned to Camp Seven Hills, at age 11. I stayed in the Highlands again, made friends who became my penpals, rode horses, cried at the closing campfire because I knew I’d never see my new friends again. The next year I stayed in Plainsmen (another stand of platform tents) and completed the high ropes course under the guidance of a counselor who called herself “Ducky” (all the counselors had nicknames). At ages 13 and 14 though, I signed up for two week sessions which included seven days canoeing the Allegheny River in Pennsylvania—sleeping on islands in the river, packing food into 5 gallon plastic buckets, pooping in holes dug with a small shovel, linking all our canoes and pitching a huge sail, letting ourselves be blown south for a little while on the more placid stretches of water. There were sections of rapids, too, I remember those because I was always so afraid of tipping over and losing my bag and food.

My sister Hannah was with me on one of the canoe trips, and my friend Ellen—my longest-time camping companion—was on both. Before and after we found ourselves in Allegheny, though, we were stationed in Woodland Way, my favorite of the Camp Seven Hills sites, tucked deep in the woods near the bottom of camp. The site was also exciting because it was near Pine Hollow—a circle of cabins that many girls claimed to be haunted. At night, sometimes, we’d look out into the woods behind our tent, looking for little orbs of light, anything that might resemble a ghost.

I’d always wanted to stay in those cabins at Pine Hollow, but never got assigned to one; it was platform tents, for me, every time. I liked to stay in the back of the tent—the cot I deemed scariest. Being near the edge, near a flap that could be opened rather than being tied down, created a level of fear that was alluring during daylight hours, and then just frightening enough to make me almost regret my choice at night. I’d lay there imagining raccoons trying to scramble up into the space beneath my cot, looking for food or treats, but it never happened to me. It only happened to other girls—we’d wake up to the sounds of screams in a neighboring tent, the counselors running in, shoeing away the animal with a broom.

After my last Allegheny trip at age 14, I stopped going to Camp Seven Hills, except once or twice more with my Girl Scout Troop during spring retreats, and just for the weekend. Once, we stayed in the Brownie Lodge, even though we were Seniors. Through high school, the only camping I did was in the woods around my house, and in friends’ backyards. In college, there was even less camping, maybe none at all. After college, though, I moved to the Pacific Northwest, fueled principally by my attraction to the mossy woods, jagged green mountains, the endless number of hiking trails and backcountry campsites to explore.

But my boyfriend and I didn’t have much money when we arrived, so we at first resorted to car camping. We bought a cheap tent and sleeping bags from Kroger, the grocery store, and hoped whenever we camped that it would not rain. We watched for sales at REI and eventually got some decent gear—and he lucked out and found a fantastic used backpacking pack at an odd little store in Snoqualmie, Washington. But my first backpacking trip did not include him. Instead, I went on an overnight to the Oregon Coast with a girl I’d met (I can’t remember where) and two of her friends. We intended to hike the entirety of Cape Lookout, sleeping at the point farthest out into the ocean before hiking back the next day. I didn’t have a proper pack yet, so tied my sleeping bag and gear to the outside of my daypack, in plastic grocery bags, and opted to share a tent with the girl who’d organized the trip.

She and her friends had the most top-notch gear. I recall her tent being Sierra Designs, which I knew was a pricey brand. I remember the guy that came with us had a new, bright red Osprey pack, and his camping stove was a JetBoil. At least some of the dinnertime conversation was about gear, comparing and contrasting brands, performance, comfort. I must have stayed silent, as I wouldn’t have had much to contribute. I felt strangely ashamed, out of place, out of my league. I’d always loved the outdoors, but it was suddenly clear (or at least it felt to me) that I didn’t have the money to love the outdoors efficiently, and certainly not in style. I felt terribly homesick, and thought longingly about my boyfriend and his used backpack, or the sleeping bags and tent we’d found on clearance—decent quality brands, but not the best, not the kind of stuff everyone around me here owned. My homesickness, though, extended far beyond my boyfriend and our discounted gear… I thought of home, our simple tent from BJ’s, or the basics provided by Camp Seven Hills. I thought of those plain, low-rolling hills in New York’s southern tier—paltry, compared the the misty coastal forest we hiked through now, with its dramatic rocky cliffs, the carpet of clover covering every inch of woods beyond the trail. But I missed those hills, and those dry hardwood forests, a lot. What made it feel so much worse was that I had not expected to.

Eventually, I found a pack on sale. My boyfriend and I did several short weekend jaunts, tying our food up in a tree, as we’d learned from our more experienced friends. One autumn weekend, friends from Rochester flew out to visit us. They bought a twenty-four pack of PBR and stuffed it into their packs. We loaned them our Kroger tent and sleeping bags, and we all hiked deep into the woods around Mount Hood. When we awoke in the morning, a dusting of fresh snow covered the ground. We built a small fire, made oatmeal, and one of the guys cracked open a beer (I think, actually, he may have mixed some of it into his oatmeal) and then we left our campsite behind to hike up a ledge below the old volcano. When we reached the lookout, the beer-and-oatmeal-eater fixed Mount Hood’s pointed, snowy peak in the viewfinder of his medium-format camera as he perched it upon his knee.

There were other notable camping trips, car-based and backpacked. In the Oregon desert, my friend Emily and I shared our tent while my boyfriend slept outside, on the sandy earth and beneath a black sky flooded with stars—the thin, dry air allowed so many more points of light to push through. The next morning, we awoke, made breakfast, and then hiked twelve miles to summit South Sister, the tallest of the volcanoes in the Three Sisters chain. Another time, in California, my sister Hannah, my boyfriend, and I, all stuffed ourselves into our tiny two-person tent in the rain before exploring the Redwoods the next morning—my twenty-fifth birthday celebration. My other sister, Ellen, and two of her friends were stuck sleeping in the minivan we’d rented, as I’d forgotten the Kroger tent at home. We ate breakfast at a diner in a town called Orick before slipping into the misty and ancient forest of huge trees.

On a short backpacking trip into the Indian Heaven Wilderness in southern Washington, I recall laying awake at night, my boyfriend fast asleep, and being overcome with a feeling that often haunted me at night, in nature, away from “civilization”. That feeling was one of absolute mortality, finality, and smallness. For some reason, camping in the woods, as much as I loved it, often forced me to remember that I was going to die, and there was nothing I could do about it. Was it because I was surrounded by trees and grass and flowers that, unlike plastic and concrete, would also certainly die and disappear? Or was it because I was away from the everyday busy-ness that kept me distracted and distant from such thoughts? Probably both. And being someone with morbid tendencies, it has never required much to remind me that no, I don’t get to be here forever. If there was ever anything I didn’t like about camping, it was when this feeling came over me as I lay in my tent at night after everyone else had fallen asleep: that I’d emerged from all that quiet darkness around me, and one day, I’d recede back into it.

When I returned to the east coast, camping hardly ever happened at first. I didn’t have any friends to go with in Rochester, nor did I know anyone with backpacking gear, or an interest in acquiring it. I dragged another boyfriend on a car-camping trip to the Adirondacks, which was surprisingly tranquil despite every campsite being booked. I also went camping alone once, booking myself a lean-to on the shores of Heart Lake in the High Peaks region. I recall that at night I was terrified of a bear trundling into camp, and opted to stay up late with my flashlight, plowing through a pile of books. I’d always fall asleep eventually, and wake up in the morning untouched by predators.

But I tired of only car camping, and opted to form a “Women’s Outdoors” group on Meetup.com. We did some easy starter hikes, and then I organized a few backpacking trips on the Finger Lakes Trail. First, we hiked into Sugar Hill State Forest and slept in a lean-to at the four-mile mark. It was perfect, almost, save for a little nighttime anxiety of a fellow camper. “I just keep picturing opening my eyes and seeing some scary man standing over me!” she said. I tried to tell her that these are the kinds of images you want to actively push out of your mind when sleeping in the woods, miles from anyone else, or any town. We did another weekend trek near Huckleberry Bog in the fall, but our trip was spoiled not only by endless pouring rain, but by having to share our lean-to with a small herd of teenaged Boy Scouts, whose feet stunk and who made it hard to be sure you’d wandered far enough before peeing in the woods. Since there were fewer of us than them, we slept in the smaller upper bunk area of the lean-to, sharing the loft with mouse turds, heaps of cobwebs, a pile of moldy old logs, and damp carpeting. To this date, that’s the last time I’ve gone backpacking.

And I do miss it. Having grown up surrounded by woods in a rural area, and having camped so much as a child, sleeping outdoors feels like an essential part of my existence. So, I’ve tried to get back into car-camping—again lacking the gear to go backpacking—but I’ve been less than thrilled with each experience.

Almost two years ago, at Ontario County Park in the Finger Lakes region, my boyfriend Bill and I encountered some of the most beautiful pine forests I’d seen in years, along with a camping neighbor who called himself “the reaper.” The site next to ours was overflowing with tents, trucks, and pop-up screens, along with bright green tube lighting, and a huge boombox pumping out hard rock and pop country. Disturbed, and disappointed at how easily all their noise (especially the howling and whooping) traveled through the sparse forest, we picked up our tent and moved it down to the hill to another empty campsite we’d found. This past June, in Watkins Glen, we booked a site on the loop farthest from the RV hookups—though RV’s could rent any spot so long as it was big enough, and they brought a generator. I was pleased that the sites were booked mostly with tents, but was disturbed by a few of the RV sites, decked out with more tube lighting, loud radios, and generators running well outside the allowed hours. Even though the RV next to us respected those rules, we could still hear the grumbling of generator motors from across the loop, well into the evening. When they finally shut off, I felt an immediate sense of relief to remember what plain old forest sounded like. I determined that the big events at the raceway that weekend had brought out more “atypical” campers than usual, and booked another state park site for a camping trip in the Adirondacks, later in the summer. An aside: it was during that trip in Watkins Glen, actually, that I encountered my first bear: in the early morning, just after walking the dog, and there it was, small and black and loping through the woods. Luckily, it turned toward the RV, instead of toward me standing next to my dog as she wolfed down her breakfast.

At Golden Beach campground, on Raquette Lake, there is no electrical loop for RVs. I thought this was because fewer campers in the Adirondacks arrived with an RV. This was, after all, my memory of camping at another state campground in the region nine years ago. But this was not the case. Nearly every site was occupied by an RV, and a huge (and often loud, rumbling diesel) truck or SUV to pull it. Bill read in a camp pamphlet that they’d had to close many sites because they were so degraded due to the weight of RVs, and the fact that the owners of those RVs often cut down branches or whole small trees to make room for their accommodations. We heard proof of this on our last day at Raquette Lake, listening as a truck tried to back an RV into a space that proved a bit too small for all thirty feet of it. We could hear twigs snapping, wheels spinning in the mud, and many times over, as it took several attempts to park the thing. I was quite irritated that I had to look at all those RVs, littering the dark and quiet woods with their white or metallic sheen, with the low growl of their generators. Many children and babies screamed day (and night). Dogs barked louder than I recalled ever hearing. Many people brought huge flags and hung them at the “entrance” to their campsite. Some sites had so much stuff it seemed like the people there were intending to stay for months (two weeks is the limit).

I felt a bit ashamed of how judgmental I was being. Who was I to determine how one should camp, or spend their free time? But my boyfriend made a good point, one evening, finally breaking the silence of his foul mood about the conditions of our stay: “I don’t get it, why go camping if you’re not even sleeping outside? What’s the draw? RVs make sense for road trips… but why bring one here, to the woods, to park it for days if you want to just be outside? And if you don’t want to be outside, why come at all?” I remarked that I wasn’t quite sure myself. And then I wondered aloud how car camping might change if the parks restricted the activity to those willing to actually camp, to pitch a tent or a hammock and cook on a little stove or over the fire. It would be quieter, there would be far fewer people, and also the parks would generate far less revenue. At the very least, I suggested, they should have a section for RVs, and then disallow them everywhere else. Our tent looked small and sheepish (as it should) pitched beneath the trees, the green rain fly blending into the foliage, the site tidy of clutter except two chairs and a tie-off stake for our dog. But at nearly every other site, junk was strewn about, noise belched its way out and into the surrounding forest, music played or generators hummed, people made a racket, made very well known their presence.

Camping for me has always been about keeping my presence small, as close to invisible as possible, so as to let the quiet of nature remind me how the Earth once was, how it still is, where there aren’t too many people around. I love music, but I also love the sounds of the woods: the whistle of wind high in the pines, tree trunks creaking, leafs rustling against each other, birds trilling and cooing and taking flight, water lapping the shore in small waves, loons moaning their sad songs in the darkness. Camping, if I have my way, should remind me of how small I am, how insignificant, and how much a part I am, of the natural world: easy to forget sometimes, when you live in a city. But, that truth is equally hard to remember when humans choose to bring so much noise and clutter and electronics along, which instead reinforces the false idea that humans are apart from nature, rather than a part of it.

On our last night, listening to yet another neighbor release thunderous belches out into the atmosphere, we were finally able to laugh about it—probably because we’d soon be leaving. How was it everyone around us felt perfectly content to make their neighbors listen to all that gas leaving their body? The two burping men played music on their radio (quietly, at least) and engaged in hours of awkward conversation. I went to bed before Bill, but he stayed up late by the fire and attempted to read—finding himself unable to focus, though, as their conversation became increasingly personal, finally ending in tears. That’s good for them, I guess, but it’s not exactly what I want to listen to when I’m sitting up at night, in the woods. The loons that night could only be heard when those men paused talking, or when a song on their radio got especially quiet. Which made me sad. I love loons, and don’t get to hear them often.

What has happened? I wondered this aloud to Bill, and later on the phone with my mom. Car camping wasn’t so obnoxious even nine years ago. I complained that now I was going to have to find other places to camp, as state campgrounds were clearly allowing RVs run the roost. But to blame RVs on the whole also isn’t exactly fair. Our neighbors at Watkins Glen who camped in an RV were, apart from running their generator during the allowed times, quiet and respectful of the experiences of those around them. While I didn’t love the fact that I had to look at (and listen) to their RV, I could respect that for them, “camping” in an RV what was worked best. And while I’d still advocate for a separate RV section at public campgrounds (I can’t be the only tent camper who doesn’t want to listen to generators), what I suppose I’m really advocating is restoring a greater sense of respect for others: other humans, and other beings—plant, animal, even rock and soil.

It seems to me (and I recognize my perspective is inherently biased and limited, as it is mine), that something we’ve lost, and continue to lose as a society and culture, is a respect and reverence for others. When you stake a huge flag at the entrance to your campsite, you’re making a declaration about your identity, your beliefs and preferences, you’re ensuring that others know something about you. Since when did camping become about letting others know more about who you are? Making yourself known doesn’t automatically qualify as a lack of respect for others, but it reflects, I think, a creeping and deepening sense of self-centeredness. And when we’re increasingly interested in representing and broadcasting who we are, might we not also lose some of our interest and curiosity about who others are? When we think that who we are is of great importance, perhaps we’re more at ease with cutting down saplings to make room for ourselves and our belongings, or spinning our wheels in the sandy soil to ensure we’ve gotten everything parked just right. Those little grains of sand we tread upon are so tiny we can hardly even pull them apart; but together they make walking and parking and pitching a tent possible.

A common and widely accepted philosophy in hiking and backpacking is that you should “leave no trace.” Wherever you’ve walked or camped for the night, no one else should be able to tell you were there. This is best accomplished when you bring as little with you to begin with. The more you have to pick up, the harder it becomes to ensure you’re leaving nothing behind. When we’re asked to leave no trace of our presence, to erase any indications that we were somewhere, we are also forced to exist in a state that takes up as little space as possible, and to confront a degree of humility about our place in the world. The animals and rocks and plants do not care about who we are, in fact, they do better when we make ourselves as scarce as possible. If we walk through forest, quietly and picking up after ourselves, no one should know we were ever there. We get to leave no marks, no indicators of our existence. And so I have to ask myself: Does this not run parallel to a terrible and perhaps universal human fear? That we’re here, on Earth, for a little while, and unless we’re extraordinarily famous, there’ll come a day when no one will know we’d ever been here at all.

It’s a stretch, maybe, but I’d rather try to understand my fellow humans than demonize them, as baffling as their behavior may be. I could write forever on how we got here, why this self-delusion about human and individual importance seems to be reaching an all-time high. I witnessed it camping, to my great dismay, but I see it on the road, observing how others drive, I see it at the doctor’s office when I have to sign a waiver agreeing, essentially, that I will not verbally abuse the staff if I do not get what I want. Human selfishness seems to be worsening, seems to be bleeding into everything we do. I think this can happen when our fears are capitalized on more frequently than our hopes or aspirations. I think this can happen when our differences are emphasized more than all that we share (and I do believe that we share more than we differ). I think this can happen we are told, and believe, that we’re better than others, that we’re special, that we deserve more, and we have the right to go out and take whatever we want. I think what is happening is that humans are increasingly suffering from the delusion that they are apart from rather than a part of the world, of community, the planet itself. And cut off from our source, death seems a much worse fate.

I think this emphasis on “me” instead of “we” can happen in all realms of life and living: easiest and fastest in traffic, at a stressful doctors visit, at the grocery store, at work, but even in nature, or at a campground. Maybe especially in nature, where we are expected or told to “leave no trace”. Maybe some of us rail against that, determined to make our marks however possible. Or maybe I’m not the only one who experiences that shiver of mortality in the quiet of my tent, after dark. Maybe when you bring more stuff or make more noise, those reminders of mortality become smaller and quieter and easier to ignore, like they often are in the rush of everyday living.

I have no proposed solution for this problem of expanding human selfishness. I have only an exercise I try to engage in when I find myself tempted to judge (or am even actively judging, as sometimes I simply cannot stop myself) others for the odd or wasteful or invasive or thoughtless things they do. As I walked around Golden Beach Campground with my sweet dog, Penny, aghast at all the noise, all the shit strewn about, all the apparent attempts to feel bigger than nature rather than humbled by it, I’d periodically force myself to interrupt the stream of judgments coursing through my mind by looking someone in the eye, squeezing out a smile. Because when I pause long enough to lock eyes with somebody, and hold that gaze, I see not only who I am more clearly, but who they are: another human, bound to death.

Leave a comment